Occupational therapy (OT) can be an abstract discipline, especially related to children. People often understand what speech-language pathologists do because their specialty is in their job title; physical therapists are well-known because many have people have received physical therapy services, whether from an injury, their child learning to walk, or their elderly parent receiving PT in or after a hospital stay. As for occupational therapy, it is often identified as ‘getting back to work’, and often people are confused as to how occupational therapists (OTs) can help their child. Occupation does mean ‘work’ but is defined as ‘the activities people of all ages need and want to do’ (AOTA). OTs, as defined by AOTA, ‘help people participate in their desired occupations with the therapeutic use of everyday activities, based on the client’s personal interests and needs.’

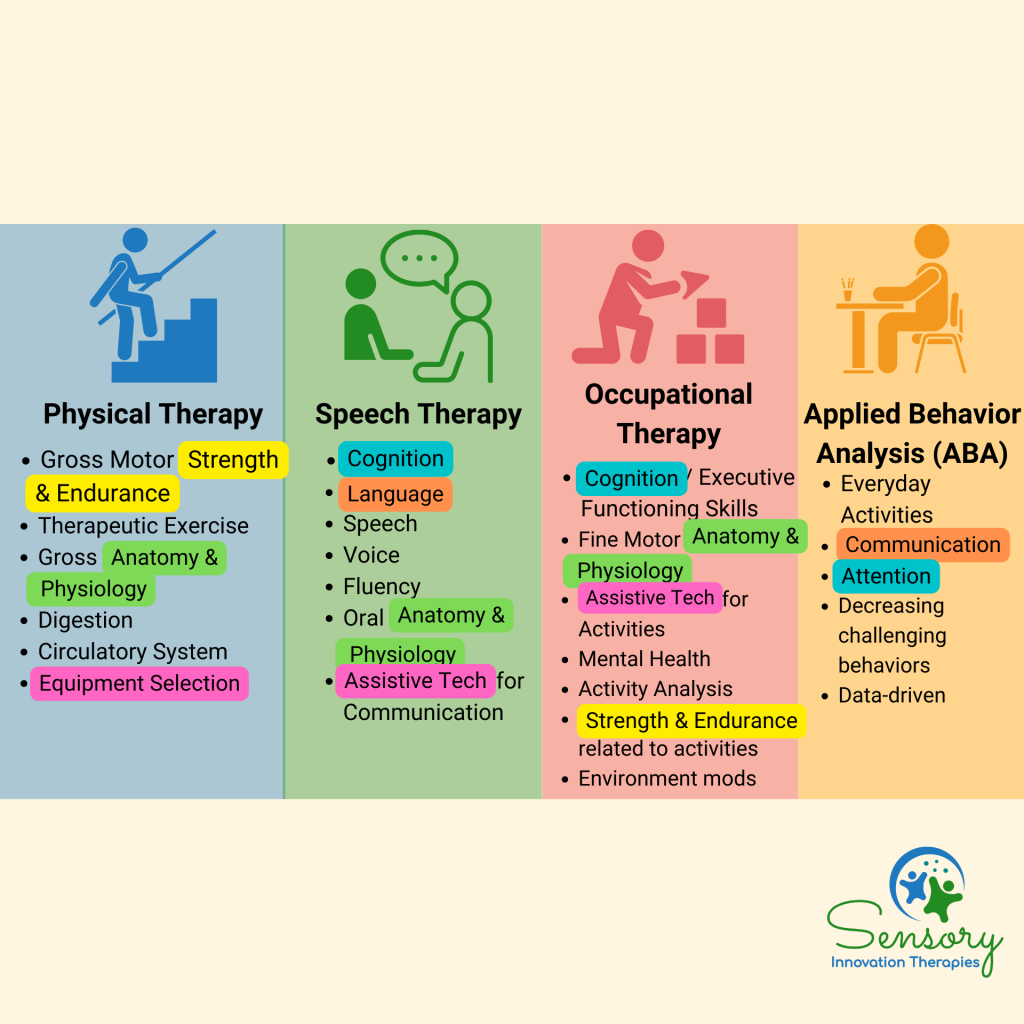

The four primary disciplines that support children with diverse learning needs include physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, and applied behavior analysis (ABA). Each discipline’s education lends itself to specialization and focus of treatment. Though differences exist between each discipline, the overlap allows for generalization across approaches. Figure 1 briefly outlines the areas of focus for each discipline, with the highlighted areas being similarities between disciplines. Occupational therapy has overlap with each discipline. OTs have strength in task analysis, or taking a task and break it into smaller parts to understand the strengths and the barriers for each individual. By breaking up the task into smaller parts, OTs are looking at all aspects of the individual and the activity to be able to accomplish the task. Thus, OTs tend to look at the whole individual, task, and environment, which tends to overlap with other disciplines.

Occupational Therapy for Kids: What Do OTs Work On?

The occupations of a child are the activities they do throughout the day. Starting with waking up, a child participates in dressing, toileting, hand washing, tooth brushing, hair brushing, eating, transitioning between activities, playing by themselves and with peers, going to school and the components of school (I.e. handwriting, coloring, cutting, attending to tasks, reading, playing at recess), and sleeping. OTs help kids access, participate in, and perform these activities.

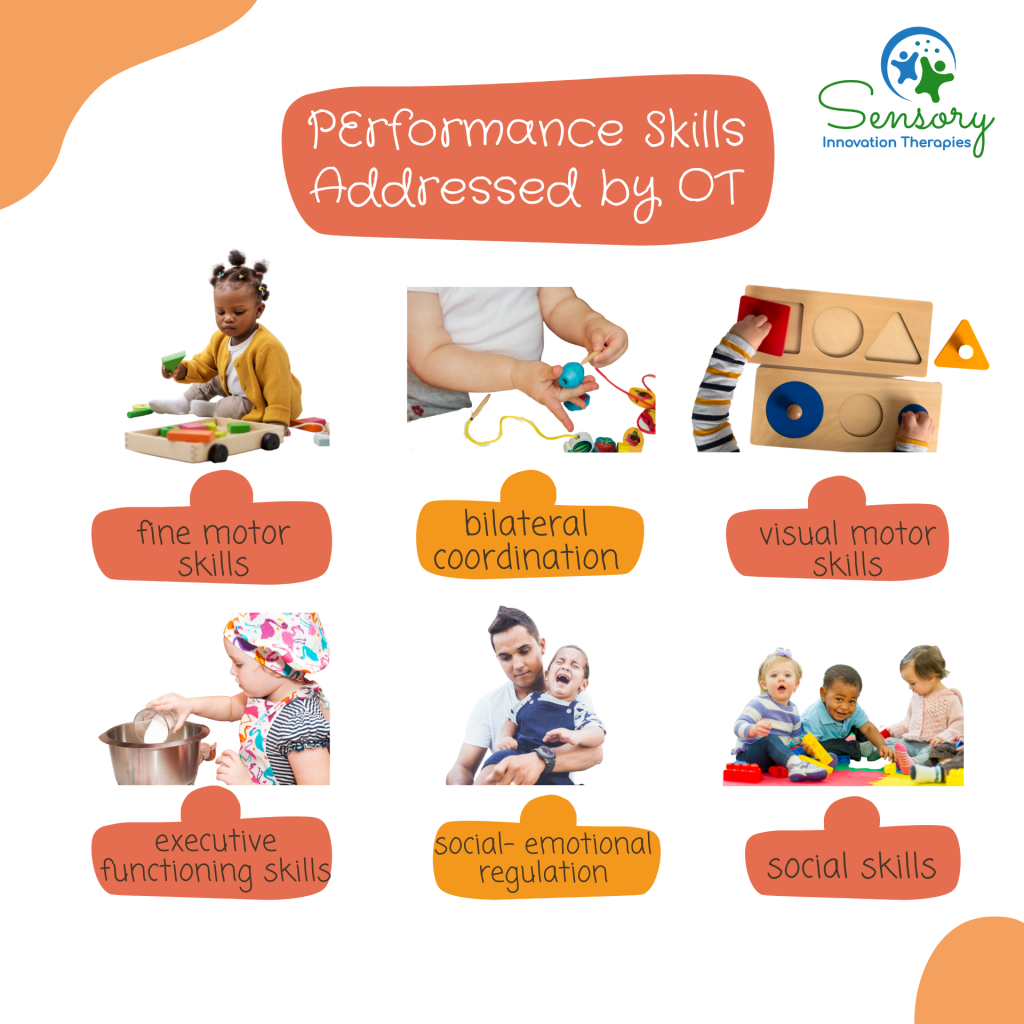

If a child is having difficulty with one or more of these tasks, OTs then look at the underlying skills that are impacting a child’s participation. In occupational therapy, these are called performance skills. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) defines performance skills as ‘observable, goal-oriented actions and consist of motor skills, process skills, and social-interaction skills.’ Figure 3 outlines the specific skills OTs assess related to meaningful activities.

Fine motor skills: the ability to control the small muscles and movements in one’s fingers and hands, face and mouth (tongue), and feet. Typically, OTs will address the muscles in one’s fingers and hands.

Visual-motor skills: the ability to coordinate one’s movements (fine and gross motor) based on the visual information one perceives and processes.

Bilateral coordination: the ability to use both sides of the body cohesively to perform a movement.

Executive functioning skills: the ability to initiate, continue, sequence, terminate, locate and gather items, organize, navigate, and noticing and adjusting during a task. Executive functioning skills are related to mental and cognitive skills needed to perform a task.

Social-emotional regulation: the ability to keep a calm, alert state when faced with challenges and obstacles, and ability to identify own emotions.

Social skills: the ability to interact with others, navigate social situations, create and maintain friendships, and play with peers.

How Does Occupational Therapy Help With Gaining Skills?

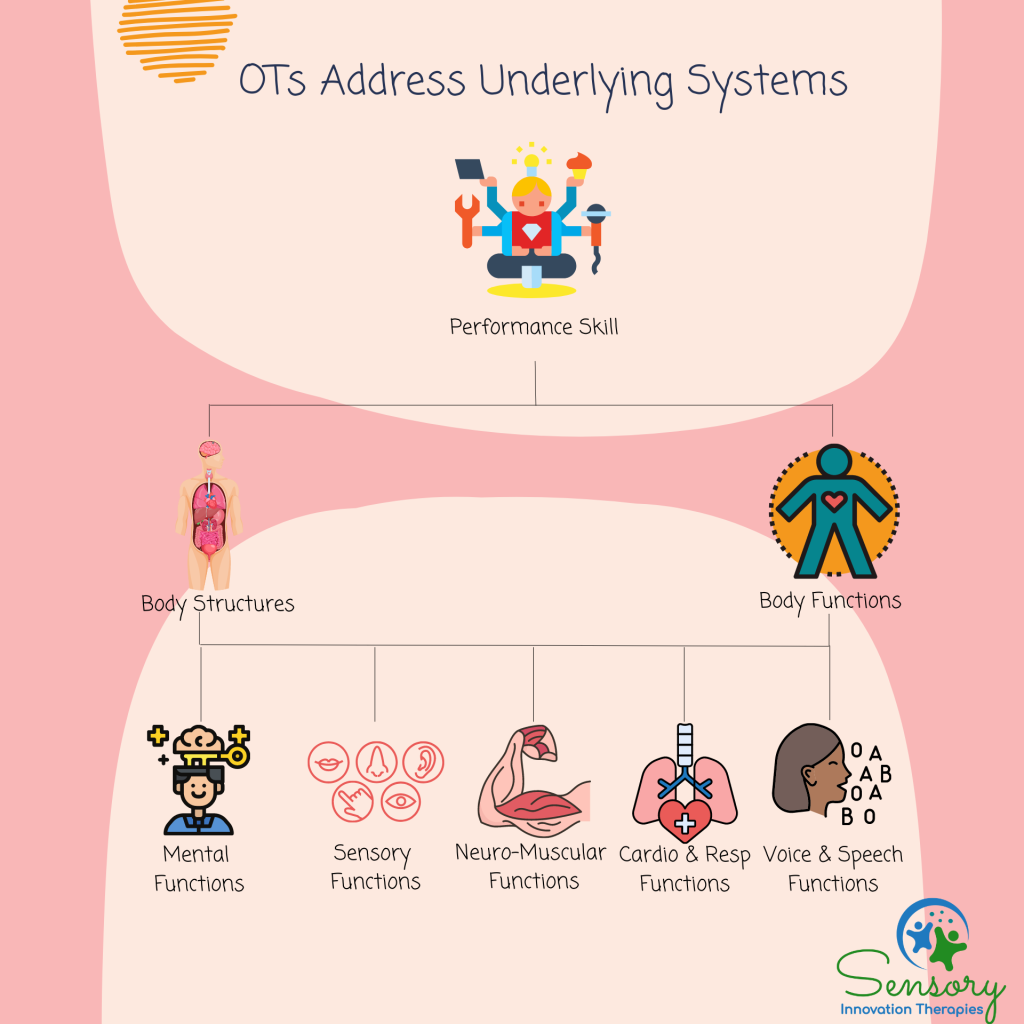

OTs address performance skills by understanding how the body structures and body functions are working, then using a child’s strengths to facilitate structures and functions that need additional support and focus. Body functions and structures are ‘physiological function of body systems (including psychological functions) and anatomical parts of the body, such as organs, limbs, and their components, respectively’ (AOTA, 2021). This would include how the overall systems of the body are functioning, and if their functioning is impacting meaningful activities. Figure 4 review the systems that impact performance skills that OTs address.

Mental functions: includes any impact on the brain’s structures, and more specific mental functions including attention, memory, perception, thoughts, complex sequencing, emotional regulation and range of emotions, experience of self and time (such as identity), alertness, orientation to person, place, and time; interpersonal skills, energy levels, and sleep.

Sensory functions: includes the functioning of the visual, hearing, vestibular, taste, smell, proprioceptive, touch, interception, pain, and sensitivity to temperature and pressure. For additional information on sensory processing, check out 8 Sensory System Activities.

Neuromuscular functions: includes joint mobility and stability; muscle power, tone, and endurance; motor reflexes, involuntary movement reactions, control of voluntary movements, and walking patterns.

Cardiovascular, hematological, immune, and respiratory functions: includes maintenance of blood pressure, heart rate, and rhythm; protection against infection and allergies; respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth; and cardiovascular endurance.

Voice and speech functions; digestive, metabolic, and endocrine system functions; genitourinary and reproductive functions: includes voice and speech functions, digestive systems, and genitourinary and reproductive functions.

How Can OTs Help With Modifying the Environment?

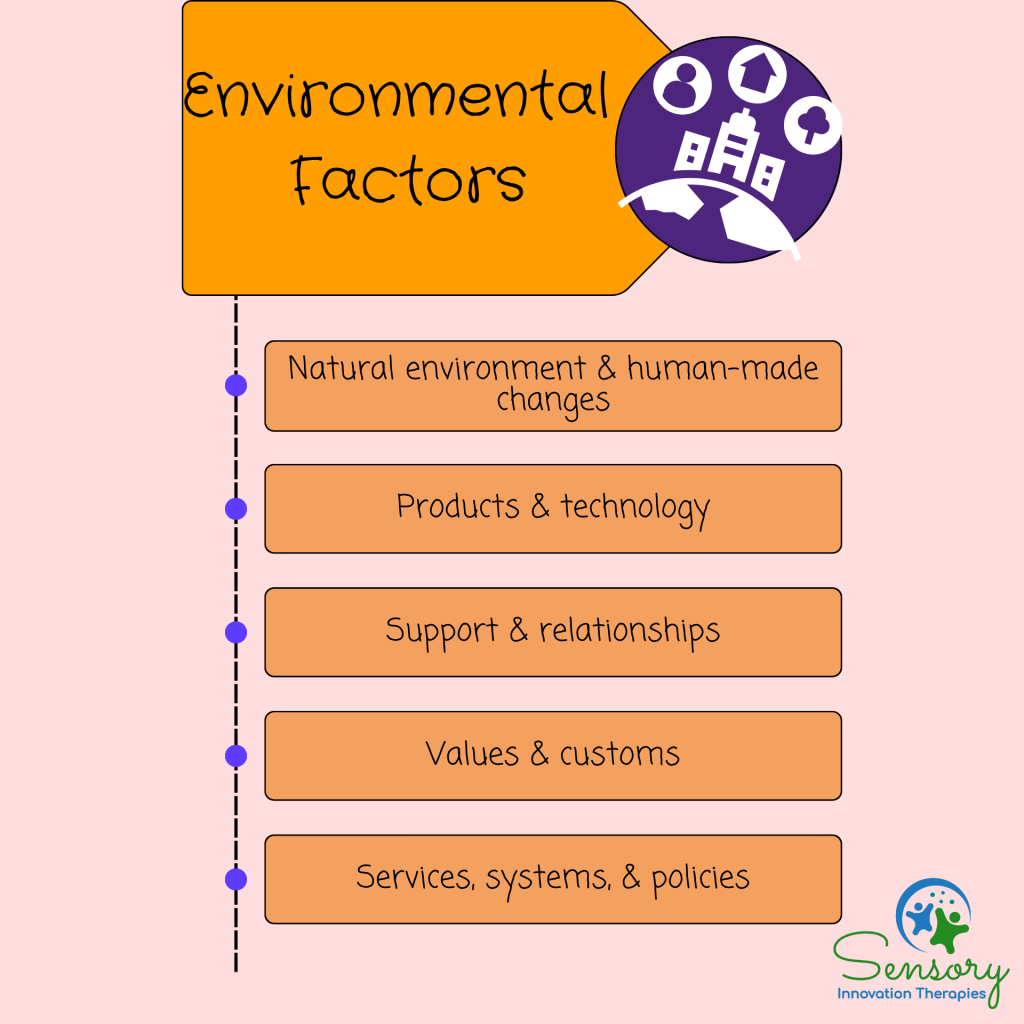

OTs assess the environmental factors that influence and impact functioning, including factors that are facilitators and barriers. Figure 5 outlines environmental factors including the natural and human-made changes, products and technology, support and relationships, attitudes, and services, systems, and policies.

Natural environment and human-made changes: animate and in-animate elements in the environment, include how a room is set up, the natural light and temperature of the environment, and any other elements in the environment that could shape participation and performance.

Products and technology: products, equipment, and technology that could be useful or impede participation and performance. This could include barriers such as utensils that aren’t the correct size and shape; by adjusting the type of utensil being used, a child could be more independent with feeding or handwriting.

Support and relationships: physical or emotional support, assistance, and connections provided by people or animals. This could include a service dog who provides emotional support for children who have emotional needs.

Attitudes: Customs, practices, ideologies, values, and beliefs held by people other than the client.

Services, systems, and policies: Benefits, structured programs, and regulations provided by institutions. This could include insurance coverage, services provided by the school district, and accessibility to the healthcare system.

What is the Goal of Occupational Therapy for Kids?

Children are referred for occupational therapy due to concerns in one or more performance area. The goal of OT is for children to participate in meaningful activities with as much independence as developmentally appropriate. Figure 6 outlines the 5 goals of occupational therapy.

Increased independence in meaningful goals is the end goal of occupational therapy. OTs do this through increasing participation and engagement in activities. When children are able to increase their engagement in activities, they are better able to participate in the activities and practice the skills needed to accomplish the activity. A piece of engagement is addressing self-regulation. Often, children receiving OT services need support with maintaining a calm and alert states. By focusing on self-regulation strategies, children become more regulated throughout the day. Maintaining a regulated state is the foundation for participating in child-perceived challenging activities.

Maintaining a regulated state also leads to increasing frustration tolerance, or not getting frustrated so easily. By increasing frustration tolerance, children can work on more challenging tasks that will shape their cognitive, social, and motor skills. By gaining new skills, children can better engage and participate in their environment with more confidence.

Lastly, for school-aged children, the goal of OT services is for children to better access educational learning. This could include modifications to curriculum to increase accessibility, or increasing the skills relevant to academics. These skills include handwriting, social participation, accessing their food during lunch, participating in art and physical education, reading, attending to instruction, and independence with transitions.

The goal of OT is unique for each child. The family and OT will collaborate on what activities are meaningful to achieve maximal participate and independence. These goals will guide OT treatment.

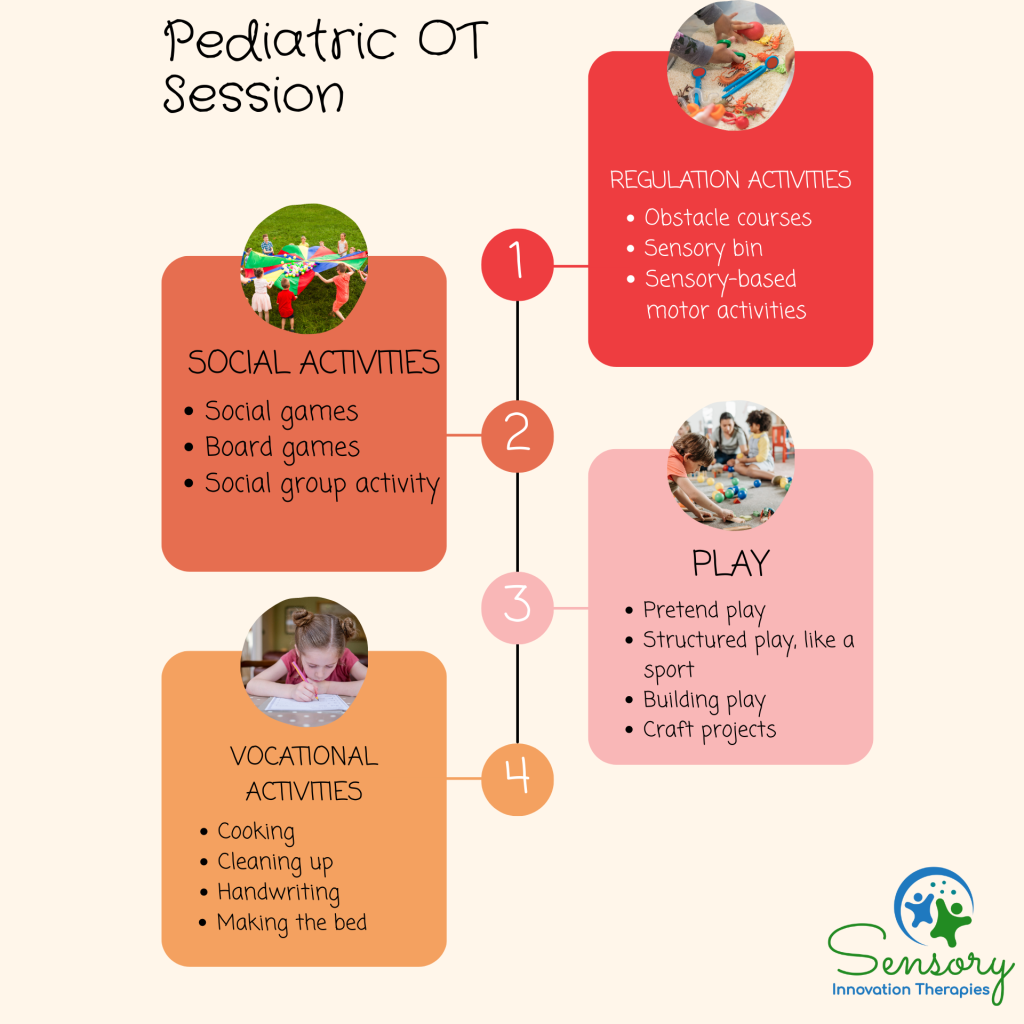

What does a typical pediatric OT session look like?

OT sessions are structured similar as OTs want to prepare the body for optimal engagement. Figure 6 outlines how a typical OT session for children may look.

Activity 1: Regulation- starting the session with regulating activities sets a child’s body up for success. Obstacle courses are a great way to regulate the body. They can include animal walks, novel movements, crashing, jumping, swinging, and providing deep pressure into the joints and whole body. Children often participate in sensory bins with dry, sticky, or wet materials, depending on what the child likes and is working on. The sensory bins can have different play materials inside of them to target visual perceptual skills and play skills.

Activity 2: Social activities– social activities are a great chance to not only work on social-interactions but to also work on motor skills and executive functioning skills. Activities include social games, like Simon Says or Mother May I; board games, such as Sorry, Candyland, Twister, or Trouble; or a social group activity where multiple kids have to work together for a common goal, such as putting together an obstacle course by themselves or creating a novel game with rules as a whole group.

Activity 3: Play- the above social activities are also in the category of play, though those would be characterized as cooperative play. For younger learners, play is focused on developing interest in play as leisure activity, developing pretend play, and participating in structured play, including playing a sport. A child’s main occupation is play and each play activity targets a range of skills. For example, participating in construction play by building items, such as Legos, not only targets the cognitive skills of play but also the motor skills involved in playing. Performing craft projects is another form of play that can target fine motor, visual-motor, bilateral coordination, and cognitive skills.

Activity 4: Vocational activities- these are task-specific activities that are either goals or have component skills in the tasks that innately address the goals. Vocational activities include dressing, brushing teeth, grooming, cleaning up after themselves, doing any chores around the home, cooking or making a science experiment, handwriting, and any other activity that may be meaningful for the child and family.

Think your child would benefit from occupational therapy? Reach out to us!

About the Author

Dr. Leah Dunleavy, M.A., BCBA, OTR/L, OTD is an occupational therapist and behavior analyst and the owner of Sensory Innovation Therapies located in South Florida’s Treasure Coast. She serves families in the home and school setting in St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach Counties. Dr. Leah has been working with the neurodiverse population for over 15 years, and has been practicing, managing, and mentoring in Chicago for the last 10 years. She has brought her expertise in sensory processing back to her hometown to support her community. Dr. Leah uses a relationship-based approach to guide families to meet their goals.